Part 1: Introduction

1.1

In this Part, we set out:

- the scope of our audit;

- what we did not cover;

- how we carried out our audit; and

- the structure of our report.

1.2

This report describes how well Waikato Regional Council, Taranaki Regional Council, Horizons Regional Council, and Environment Southland (the four regional councils) manage freshwater quality in their regions.

1.3

We audited the four regional councils in 2011 and published a report.1 In that report, we described the four regional councils' approaches to managing the effects of land use on freshwater quality. Overall, the effectiveness of these approaches varied.

1.4

In our 2011 report, we made recommendations to all regional councils and unitary authorities. These included that they:

- review methods for reporting freshwater quality monitoring results;

- have specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound objectives in their regional plans and long-term plans;

- be able to demonstrate that they effectively co-ordinate efforts with stakeholders to improve freshwater quality; and

- review their delegations and procedures for prosecuting non-compliance, to ensure that any decision about prosecution is free from actual or perceived political bias.

1.5

Since our 2011 report, the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (the National Policy Statement) and its amendments have superseded some of the issues we raised. Therefore, this report is not a straightforward review of how the four regional councils have responded to our 2011 recommendations. It provides our updated view on how well the four regional councils:

- set objectives for freshwater quality;

- gather and use freshwater quality information; and

- ensure effective compliance with the Resource Management Act 1991, relevant provisions of their regional plans, and resource consents.

1.6

We describe where the four regional councils are succeeding and identify issues, potential risks, and opportunities for improvement.

Scope of our audit

1.7

Our audit focused on how well the four regional councils manage freshwater quality.

1.8

We selected the four regional councils based on:

- the extent and significance of surface water resources in their regions; and

- freshwater quality trends and pressures in their regions.

1.9

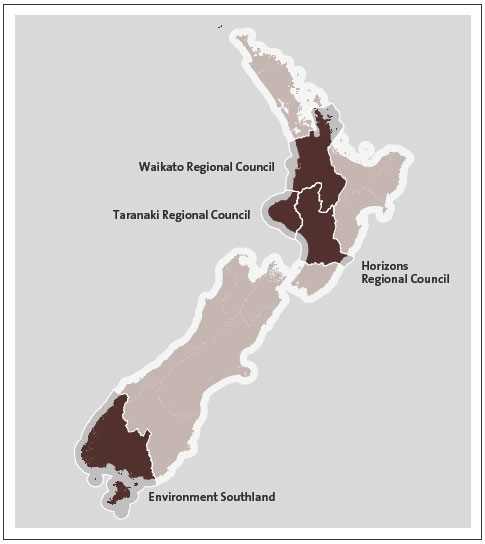

Together, the four regional councils' regions cover nearly one-third of the country's total land area (see Figure 1). The Waikato region includes the country's longest river (the Waikato River) and largest lake (Lake Taupo). The Taranaki region has more than 300 short but fast-flowing streams and rivers. Horizons Regional Council's region includes the Whanganui, Rangitikei, and Manawatū river systems. The wet climate in the Southland region has meant that significant artificial drainage has needed to be installed on pastoral land.

Figure 1

The four regional councils' regions

A map of New Zealand that shows the location of the four regional councils' regions. The map shows that the four regions together cover nearly one-third of the country's total land area.

Source: Land & Water New Zealand.

1.10

As we noted in 2011, the four regional councils have their own unique contexts and challenges. They have different topography, landscapes, soils, and river gradients. The historical quality of their freshwater, the degree to which land use has intensified, and the funding available to manage freshwater quality also varies.

1.11

Communities' desires guide the actions regional councils take to respond to freshwater quality concerns. The approaches taken to maintaining and improving freshwater quality in one region might not be enough or needed in another region.

1.12

We looked at how the four regional councils manage the effects of diffuse pollution (for example, animal effluent) from intensified land use (such as intensive dairy farming), which is a major cause of freshwater quality degradation.2

1.13

We also considered how well the four regional councils work with district and city councils in their regions to manage urban discharges, such as from wastewater treatment plants.

1.14

This report presents an opportunity for all regional councils and unitary authorities to consider their success, challenges, and potential for improvement in the matters we looked at.

What we did not cover

1.15

Because there are many different aspects to managing freshwater quality, we have needed to limit the scope of our audit. In particular, we do not consider drinking water, irrigation, freshwater clean-up funds, or stormwater. We have reported on these aspects of freshwater in their own dedicated reports.3

1.16

We have also been careful not to duplicate the work of other organisations, such as the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. We had suitable technical experts to help us consider information about the states and trends of freshwater quality in the four regions and to provide a view on how fit for purpose each council's approach to monitoring freshwater quality was.

1.17

Similarly, we did not look at how the four regional councils have implemented the National Policy Statement. That has been the focus of considerable work at the Ministry for the Environment (the Ministry).

1.18

We make no comment about whether freshwater quality has improved or declined in the four regions since 2011. The science of freshwater quality is complex. Some factors that can result in declining or improving trends in freshwater quality can take many years, even decades, to have an effect. This time frame and the magnitude of effects varies within and between regions depending on local conditions of climate, topography, and geology.

1.19

The current states and trends of freshwater in the four regions are the result of cumulative actions over an extended period of time rather than the four councils' work since 2011.

How we carried out our audit

1.20

To carry out our audit, we reviewed documents such as regional plans and policy statements, compliance policies and reports, water-related policies, annual reports, state of the environment reports, and council minutes. We also asked the four regional councils to complete a self-assessment of their performance against matters we focused on in our audit.

1.21

After we received the self-assessments, we reviewed additional documents and interviewed council staff and elected members about their roles in managing freshwater quality policy and operations.

1.22

We also spoke with representatives from hapū, iwi, territorial authorities, the farming sector, and environmental groups about their experiences working with their regional councils on freshwater quality management issues.

1.23

We met and worked with staff from the Ministry, who provided us with data about the current freshwater quality in the four regions and information about the medium-term and longer-term trends.

1.24

We commissioned National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Limited (NIWA) to provide an assessment the effectiveness of the four regional councils' freshwater monitoring networks and approaches.

1.25

We met with staff from Statistics New Zealand, the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, and the Ministry for Primary Industries. Staff from these organisations gave us their perspective on the context for the work that regional councils do.

1.26

We looked at data that the four regional councils recorded and supplied, including data on compliance monitoring results, enforcement tool use, and progress reporting on non-regulatory initiatives.

Structure of the report

1.27

In Part 2, we provide an introduction to freshwater quality management. We describe the causes of freshwater degradation and how freshwater quality is managed.

1.28

In Part 3, we discuss the incomplete national picture of freshwater quality, how this affects our current understanding of challenges to protecting and improving freshwater quality, and the action needed to address this problem.

1.29

In Part 4, we discuss the four regional councils' freshwater quality monitoring activities and NIWA's analysis of their monitoring networks. We also discuss the effectiveness of the four regional councils' efforts to incorporate mātauranga Māori and citizen science initiatives into their monitoring programmes.

1.30

In Part 5, we discuss how the four regional councils use freshwater quality monitoring information to inform how they manage freshwater quality.

1.31

In Part 6, we discuss how the four regional councils provide information on freshwater quality to their communities.

1.32

In Part 7, we discuss how well the four regional councils consult with communities to seek their aspirations for freshwater quality. We describe the progress that the four regional councils have made in updating their regional plans and setting freshwater quality objectives that reflect those aspirations.

1.33

In Part 8, we discuss the four regional councils' working relationships with different parts of the community, including people whose land use affects freshwater quality and people who are wanting improvement.

1.34

In Part 9, we discuss how well the four regional councils work with resource consent applicants and land users to understand the Resource Management Act, plan rules, and resource consent conditions. We also discuss the effectiveness of programmes that monitor consent holders' compliance with these rules and conditions, and the effectiveness of the four regional councils' enforcement approaches when consent holders have not complied.

1.35

In Part 10, we discuss how well the four regional councils carry out non-regulatory initiatives, work with the farming industry to support positive environmental outcomes, and integrate their regulatory roles and non-regulatory initiatives.

1: Office of the Auditor-General (2011), Managing freshwater quality: Challenges for regional councils, Wellington.

2: Gluckman, P (2017), New Zealand's fresh waters: Values, state, trends and human impacts, Wellington, at www.pmcsa.org.nz; Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (2016), The state of New Zealand's environment: Commentary by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment on Environment Aotearoa 2015, at www.pmcsa.org.nz.

3: These reports are available at www.oag.govt.nz.