Part 3: Measuring the improvements made

3.1

In this Part, we discuss:

- why measuring achievement of improvements is important;

- how improvements have not been measured;

- how limited information indicates some improvement; and

- what improvements people say have been made.

Summary of our findings

3.2

The Ministry has not taken a structured approach to measuring and reporting improvements from the three projects. Therefore, the Ministry cannot accurately determine how effective its investment has been or what the challenges to making further improvements are.

3.3

Limited information about the Ministry's overall performance and the views of some people using these services indicate some improvements to these court services. However, the Ministry and some organisations disagreed about what improvements have been made. In our view, the lack of accurate information about the improvements made is likely to have contributed to this.

Why measuring achievement of improvements is important

3.4

We expected the Ministry to have set out the improvements expected from each project and to track and report on achieving those improvements over time.

3.5

Measuring improvements is important because the Ministry can use this information to see whether the projects are achieving the desired results. The Ministry can also use this information to make informed decisions about whether it needs to make further changes.

3.6

Measuring improvements also means that the Ministry can demonstrate to others what the projects are achieving. This can help increase organisations' and the public's confidence in the Ministry's ability to improve court services and in its leadership of the justice sector.

3.7

The Ministry can also use this information to provide Parliament, people and organisations involved in the justice sector, and members of the public with an account of how effective the Ministry's investment in modernising courts has been.

Improvements have not been measured

3.8

The Ministry did not take a structured approach to measuring and reporting on the achievement of improvements for the three projects. This means that the Ministry cannot accurately determine whether its investments have been effective and what the challenges to making further improvements are.

3.9

The Ministry identified the improvements it expected for each of the three projects. It could have used this information to determine how successful each project has been in achieving its goals over time.

3.10

However, the Ministry did not put in place performance measurement frameworks to see whether improvements had been made. Therefore, it is not possible for the Ministry to accurately determine how effective its investment in these three projects has been.

3.11

The lack of accurate information about whether the three projects made improvements also meant that we were unable to calculate a return on investment for any of them.

Limited information indicates some improvement

3.12

Because the Ministry did not measure and report on improvements from the three projects, we looked at other information that could provide some insight.

Information about the Ministry's overall performance in its annual report

3.13

The Ministry has outcome and performance measures in its annual report that provide a high-level account of its performance during the past year. We looked at two areas in the report: "Increased trust in the justice system" outcome measures and "Vote Courts" performance measures. These measures indicated that there were varied results. In some areas, court services had improved during the past year, but these measures do not provide information about how much modernising courts has improved court services.

Information for activity levels for the three projects

3.14

The Ministry has collected activities data on the three projects. This data included the number of applications or claims made, how long it took to deal with applications or claims, and information about the use of AVL.

3.15

Activities data can sometimes provide useful indicators of effectiveness. The Ministry said in a literature review that increased usage rates were important for realising financial benefits.6 This was because maximising cost savings relied on high levels of use.

3.16

However, there were weaknesses in the Ministry's activities data for the three projects. For example, to calculate the usage rate for each District Court that provides AVL, the Ministry divided the number of AVL appearances that have occurred (actual events) by all court appearances that could have used AVL but did not (potential events).

3.17

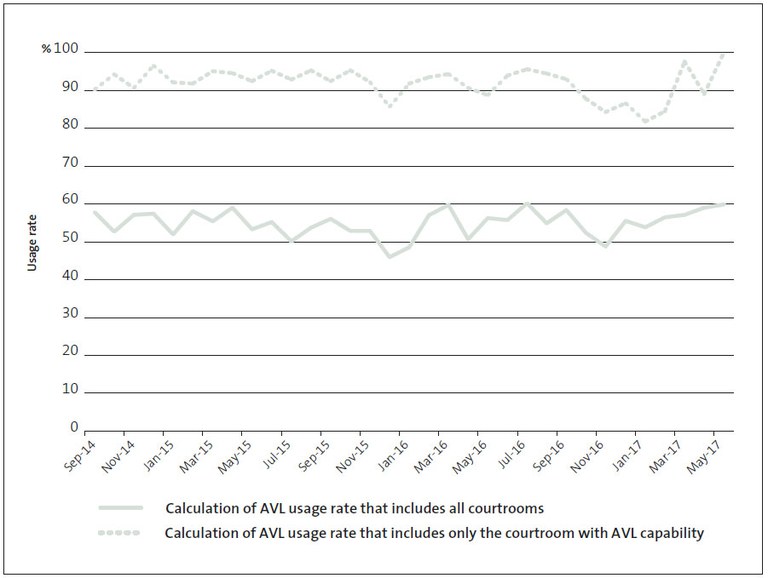

This calculation to determine AVL usage rates is flawed because the Ministry overestimates the number of potential events. The Ministry includes all courtrooms in a District Court, including courtrooms that do not provide AVL, in its calculation.

3.18

Calculating usage rates in this way has resulted in the Ministry underestimating the usage rate of AVL, particularly for larger courts. For example, for Christchurch District Court, when potential events were limited to the courtroom with AVL, the usage rate changed from about 55% to more than 90% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Comparing two different calculations of the usage rate of Audio-Visual Links in Christchurch District Court, September 2014 to May 2017

3.19

There were also weaknesses in the activities data for applications to dispute a fine and civil claims. This is because the information was too high-level and did not give a sense of the effect of changes to processes on improving services. The Ministry has recognised this and is continuing to work on it.

Operational information the Central Registry collects

3.20

We were told that the Central Registry collects data that includes the number of applications received, how fast it deals with applications, and the decisions made. The Central Registry has a target of dealing with applications within 24 hours if all the information received is correct.

3.21

Ministry staff indicated that 90% of applications to dispute a fine were dealt with within 24 hours. The Central Registry uses this type of information to allocate its staff to the various major tasks, such as dealing with applications to dispute a fine or dealing with civil claims, based on where there are pressures on the service.

3.22

Although collecting data to support operational targets is important, it does not accurately measure whether customer service has improved.

What improvements people say have been made

3.23

To understand what has been achieved, we spoke to people from the Ministry, the judiciary, lawyers, the Police, Corrections, the Inland Revenue Department, and some other prosecuting agencies. They held a range of views.

3.24

In some instances, there was disagreement between the Ministry, a sector partner, and some organisations about what improvements had been made. In our view, the lack of accurate information about improvements is likely to have contributed to this.

3.25

For centralising dealing with applications to dispute a fine, the people we talked to generally agreed that improvements to customer service have largely been made. For example, two prosecuting agencies told us that centralising dealing with applications to dispute a fine has created a more user-friendly and faster service.

3.26

However, for dealing with civil claims, Ministry staff and some affected organisations did not agree on what improvements had been made. For example, Ministry staff believed that people and organisations using this service receive more consistent decisions and processing times, have a good understanding of the process, and benefit from having a central point of contact.

3.27

Although some organisations using the service agreed in principle with centralising the process, they believed that the service they receive has not improved. We were told that they felt the processing time for some claims has slowed down or is variable and that the Central Registry is not always able to track the progress of a claim. Sometimes, claims are lost and need to be resubmitted, or claims need reworking because of changes to the process that have not been communicated to the organisation.

3.28

For AVL, people we spoke to agreed that some improvements have been made:

- Improved welfare of people in custody awaiting trial. AVL reduces the stress levels many people in custody feel when attending court. Other improvements include reduced disruption to people in custody attending their programmes and improved participation at each stage of the process.

- Improved safety and security for people in custody awaiting trial and the public. AVL reduces the risk of people in custody carrying contraband. People in custody are considered to be safer because the risks associated with travelling to court are avoided. There is also less risk of people in custody escaping, which improves public safety.

- Improved court security. AVL provides improvements in situations involving high-risk defendants. This increases safety for people involved in the court process, including members of the public. However, some people told us that these improvements need to be balanced against the fair delivery of justice.

- Efficiency gains for lawyers from using instruction suites. Instruction suites allow lawyers to consult with their clients through AVL before a court appearance. Lawyers told us that using instruction suites means that they do not have to travel to Corrections facilities to see their clients. The instruction suites also give lawyers more access to their clients, allowing them to build a relationship with them.

3.29

There was disagreement about the achievement of some improvements:

- Whether District Court days ran more smoothly. Some people believed that the AVL booking system, which allocates court appearances to fixed 15-minute time slots, reduces the need for lawyers and family members to wait in court because they know what time the court appearance is planned for. However, other people told us that the fixed 15-minute time slots could mean fewer court hearings in a day because not all hearings need 15 minutes.

- Whether there were financial benefits. The Ministry told us that it believed that Corrections has achieved some financial benefits by not having to transport people in custody to court. However, Corrections told us that they had not gained significant financial benefits. Although fewer people in custody are making in-person court appearances, this does not necessarily mean that fewer vans are going out. Each van holds up to eight prisoners, so vans carrying fewer people in custody still go to court. Corrections said that, to achieve significant financial benefits, the scheduling of AVL appearances would need to change.

6: Ministry of Justice (2016), Optimising Audio-Visual Links between court and custody: A literature review.