Part 3: How Kaipara District Council set up the wastewater project

3.1

Having decided that Mangawhai needed a reticulated wastewater scheme, KDC then had to consider the type of contracting approach it would use, how it would manage the project, and how it would fund it. These early decisions shaped the rest of the project, and so we wanted to understand how and why they had been made.

3.2

In this Part, we discuss:

- the initial advice KDC received on how to deliver the wastewater scheme and its funding constraints;

- initial KDC decisions to select a project manager through a tender process and to set up project governance arrangements;

- how KDC decided to proceed with a PPP approach; and

- our comments on this stage of work.

3.3

In summary, we conclude that:

- KDC's decisions to contract an expert project manager and to do so by tender were reasonable. Beca preparing the tender documents and then submitting a tender created the risk of a conflict of interest. Beca told us that it took steps to manage this risk.

- KDC did not fully explore all its available options for funding the wastewater scheme. It concentrated on ways of borrowing and PPP arrangements involving private sector financing rather than considering whether it could also increase its revenue to pay for the scheme. As a result, KDC's high-level analysis of the methods available to deliver the project was flawed.

- KDC was unduly influenced by financial considerations and did not fully evaluate its options for the delivery of the project, and their risks and benefits, when it decided to proceed with a PPP approach.

- KDC's record-keeping in support of the project and its decision-making processes were poor.

- Important decisions appear to have been taken informally.

- KDC does not appear to have fully appreciated the responsibilities it was taking on as the ultimate purchaser of the advisory services and the scheme. The scope of services the project managers would provide under the contract was limited, and KDC needed to ensure that it had enough overview of the project to understand its broader risks and need for additional advice. Instead, it seems to have proceeded on the basis that the project managers would deal with every aspect of the project.

- KDC failed to identify how it was going to manage the project. No group or individual within KDC was responsible for the project. By default, this later became the role of the Chief Executive personally.

Initial advice about how to deliver the wastewater scheme

Advice about levels of debt

3.4

Since 1996, the Local Government Act 1974 had required councils to comply with a set of financial management principles, including the principle of maintaining debt at a prudent level. Each council was required to have a borrowing management policy that included any specific borrowing limits set by the council. KDC set out its borrowing management policy in its Treasury Management Policy. It set a limit on borrowing using an income-to-debt ratio of 2.5:1. That is, for every $1 of debt, KDC needed to have $2.50 in income.

3.5

In June 1999, KDC commissioned a financial consultant, Mr Larry Mitchell, to review its ability to borrow. Mr Mitchell identified that, at that time, KDC's operating expenditure was nearly equal to its income. In 1997 and 1998, KDC had cash flow deficits because it had bought assets. In 1997, the income-to-debt ratio had been 5.5:1, but this changed in 1998 to 3.8:1 and was forecast to be 2.9:1 in 1999. Mr Mitchell also noted that KDC's income-to-debt ratio was forecast to be below its borrowing limit in 2000, unless KDC's income increased.

3.6

Mr Mitchell noted that KDC's income and wealth were low compared to other councils. He advised that the fragile nature of the local economy constrained KDC's ability to have higher levels of debt.

3.7

Mr Mitchell's report concluded that, based on an annual income of $16 million, KDC would be able to borrow up to $5.95 million if it was to stay within its income-to-debt ratio. He noted that KDC's tentative projections at that stage were that it needed $10 million of debt to contribute to the capital development plans of over $30 million. His view was that, if KDC wanted to increase its debt levels to $10 million and stay within the income-to-debt ratio, it would need to increase its income to $25 million. He noted that:

The strategies that might achieve higher revenues are beyond the scope of this study. They include all forms of additional revenue from charges and rates. Realisation of investments and reserves would reduce the borrowing necessary. Reductions in working capital would assist. By far the most promising option though, one which does not require such large increases in revenue, is to finance development from development contributions or some other form of third party financing. Based on the calculations of the income to debt ratio, all options will need to be explored with no stone left unturned. Preliminary projections for the next [long-term financial plan] indicate that it will only work if all means of boosting income, including third party financing are implemented.

3.8

He advised KDC that:

Given the very significant costs of proposed works and with the realisation that the upper limits of borrowing will likely be tested, alternative funding sources must be fully explored. These alternatives include the more radical forms of third party joint venturing, varying ownerships or proportions of ownership options, franchising, BOOT schemes and other "off balance sheet" strategies.

3.9

He also noted that:

It is extremely unlikely even at first glance given the sums involved that Council debt alone will be sufficient to finance the high level of proposed expenditure. Consideration of a combination of a number of sources of funds and consideration of rating increases may be necessary.

3.10

Mr Mitchell advised that:

In short the District's ability to pay is low but the future demands will be high. Taken as a whole the circumstances of the Kaipara District will require financial decision-making which is both cautious and conservative. Prudent debt levels will translate into a balance being set to achieve development but at a rate and of a size that the District can sustain. Even at first glance there appears to be little room for manoeuvre.

3.11

KDC's Management Accountant, after reviewing Mr Mitchell's paper, recommended to the Chief Executive that the concept of third parties and developers funding Mangawhai's capital development needed to be explored. In his view, "Council's funding of the entire $15 million is quite simply unaffordable." He also reiterated the report's conclusion that "borrowing will need to be undertaken in a cautious and conservative fashion and should not attempt to test the upper limits".

Funding

3.12

Several months after KDC received the report from Mr Mitchell, KDC staff met with Beca in October 1999 to discuss how KDC could construct the infrastructure identified in the Mangawhai Infrastructural Assets Study. The minutes of that meeting record that the Chief Executive advised that:

Council's major issue is that the Local Government Act 1974 does not permit the debt levels needed to fund the provision of the infrastructure. Options include BOOT (Build, Own, Operate, Transfer), DBO (Design, Build, Operate), DB (Design, Build, with Council operating), amalgamate with another Council.

3.13

KDC staff asked Beca to prepare a strategic plan for implementing the infrastructure, including options for funding, for the Council to consider at its meeting in December 1999. The contract with Beca noted that the funding options identified for the wastewater and water supply systems were:

- funding by KDC;

- PPP with KDC acting as the community's agent; or

- PPP with no direct ongoing KDC involvement.

3.14

The Strategic Implementation Plan (the Plan) was actually presented to councillors in April 2000. The Plan Beca provided stated:

The two major financial issues affecting project delivery are the level of debt funding KDC can provide for the project and the burden overall project funding will place upon existing ratepayers. … KDC may be able to raise up to $1.5 million as capital and some further funding may be available through the Harbour Board endowment fund. However this will fall well short of the $10.9 million dollars (capital expenditure) required for the wastewater reticulation and treatment project.

3.15

Under the heading "Strategic Drivers", the Plan also stated:

KDC operates within its Treasury Management Policy that sets limits on debt in relation to income. The application of that policy means KDC cannot fund capital expenditure sufficiently for delivery of infrastructure development in Mangawhai under a traditional design-documentation-bid-construct project delivery system.

Project delivery methods

3.16

The Plan outlined several methods for delivering the project, including the traditional design/construct approach and different types of PPPs. The Plan did not recommend that the Council adopt a particular type of method. Instead, it recommended that more work be carried out to refine the project delivery method. The Plan later stated that:

The assistance of private sector investment is required for the provision of this infrastructure due to the demands that this level of expenditure places on Council.

3.17

The Plan noted that the strategy proposed:

… is designed to arrive at the best combination of private sector and public (KDC) participation/risk transfer in the project to achieve the best result for KDC and the Mangawhai community, within governance constraints set by KDC and any legal/regulatory requirements.

3.18

Beca proposed to test that this was the case by comparing it against KDC delivering the project through traditional procurement methods.

3.19

Beca advised that the costs for delivering the project using traditional methods (that is, a design/construct approach) were usually in the range of 10% to 20% of the capital expenditure on the project. For this project, that cost would represent around $1.5 million to $2.0 million. However, costs using a PPP could be lower. Beca noted that the project delivery costs for previous projects using a PPP had been about 3% to 10% of the capital expenditure on the project. Beca stated that KDC's costs for the project would be expected to be between $500,000 and $800,000. Beca also advised that, by using a PPP, cost over-runs could be substantially reduced or eliminated while total project costs (that is, whole-of-life capital and operating costs) could be reduced by up to 20%.

Other issues

3.20

In the Plan, Beca also provided advice about how the project could be managed, an indicative project process if the private sector were to be involved, and a suggested time line.

3.21

Beca noted that, if the scheme involved discharging effluent to the coastal marine area, the Minister of Conservation would need to approve it. However, land-based disposal would require only resource consent from the NRC. Beca noted that:

In the circumstances the strategy should deliberately exclude discharge to sea as a practical option. As with the reticulation and treatment, the strategy should be for the private operator to be responsible for investigation of the site and method options and for seeking consents on behalf of the Council, with the Council undertaking to acquire if need be whatever land is required.

The Council's decisions on next steps

3.22

Beca presented the Plan to a Council workshop on 26 April 2000. At its next formal meeting on 24 May 2000, the Council made several decisions, including to:

- tender the project management of the implementation of the Mangawhai Infrastructural Assets Study;

- appoint members to a project steering team; and

- establish a Community Advisory Group.

3.23

Although there was no explicit decision to this effect, the Council implicitly accepted the advice in the Plan to explore PPP options. This was in line with the earlier advice of Mr Mitchell and the views of KDC officers.

Tender process to appoint a project manager

3.24

After the May meeting, KDC staff asked Beca to prepare the tender documents for the project manager role.

3.25

The request for proposal (RFP) for this role was advertised in July 2000. It stated that KDC was "seeking experienced Project Managers who have proven experience in delivering infrastructure projects within a rural community using private sector investment, whilst addressing the strategic drivers". The proposed scope of work was from developing the project scope at the start of the project up to the awarding of the contract to a preferred bidder.

3.26

The RFP explained that the exact type of PPP had not been determined. The project manager would be required to analyse potential PPP delivery methods and provide advice to KDC on the most appropriate method for delivering the project. The RFP also noted that "Private sector involvement in the financing and operation of the project are considered essential for the overall success of the project."

3.27

The RFP required each tenderer to submit its tender in two envelopes. The first envelope would contain the proposal and the second envelope the commercial terms and cost. The RFP set out that the second envelope would be opened only after the preferred tenderer had been selected. Negotiations would then begin, based on the terms contained in that envelope. If negotiations were unsatisfactory, KDC could then move to the second-ranked tenderer.

3.28

Tenders closed on 7 August 2000. Six bids were received, including a bid from a consortium led by Beca. KDC could not find any documents in its files about how it evaluated the tenders, so we have been unable to check whether KDC used the evaluation process set out in the RFP or assess how well the process was carried out.

3.29

Beca told us that, although it provided the draft RFP to KDC, KDC officers managed the procurement process, including evaluating the tenders and selecting the successful tender. Beca told us that it had no dealings with KDC until it was notified that its tender was successful. Beca told us that it was aware of the potential for a conflict of interest and that it took steps to ensure that it had no dealings with KDC during the tender process.

3.30

On 15 August 2000, KDC's Assets Leader and Regulatory Support Officer advised the Chief Executive that the tenders had been evaluated and that Beca had been selected because:

… the company has been involved with the study from the beginning, they know Council and the area well, they have extensive experience with similar projects in New Zealand and overseas, and they have the staff with the ability to undertake the management of the project.

3.31

KDC's former Chief Executive told us that:

The Council found that there was little expertise in the delivery of PPPs and BOOTs in New Zealand. However, there was a great deal of expertise in Victoria, Australia where there was a significant history of the delivery of water and wastewater schemes using the BOOT model.

3.32

At its 27 September 2000 meeting, the Council considered and adopted KDC officers' recommendation to appoint Beca as the project manager. The cost of the project management services was $617,000.

3.33

Beca proposed that a consortium carry out the work. The consortium included three Australian-based organisations: EPS, Blake Dawson and Waldron (lawyers), and an Australian-based branch of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC (Australia)) (financial advisers). Their roles were as follows:

- Beca was to supply the project director and technical manager, as well as services including project verification, consenting and communications, and technical evaluation.

- EPS was to take the lead role in the commercial management, documentation, and contract negotiation phases of the project, and have the role of "commercial adviser".

- Blake Dawson and Waldron were to provide legal advice with support from Bell Gully in Auckland.

- PwC (Australia) (apparently with assistance from a New Zealand-based partner of the firm) was to provide financial advice – in particular, detailed financial modelling, taxation and corporate finance advice, and "an overview of risk management and commercial perspectives".

3.34

Beca and KDC signed the project management contract on 2 November 2000. As we discuss later in the report, the contract was extended several times to include other work.

3.35

Beca told us that, although the contract was between Beca and KDC, all of the members of the consortium provided advice directly to KDC rather than through Beca. It told us that, in terms of the work actually carried out for the project:

- Beca was responsible for providing technical advice, including the engineering description of the benchmark, chairing and facilitating Community Liaison Group meetings, chairing and recording minutes of the Project Steering Committee meetings, technical review of the engineering design of the bids received, technical auditing during construction, providing supporting information for subsidy applications, and providing a person on secondment to act as KDC's community liaison officer.

- EPS provided advice about project delivery models (including risk profiles for the different models), provided advice about the "commercial conditions of contract", managed the procurement process, carried out commercial evaluation of the bids received, negotiated the final contract, and administered the delivery contract by carrying out the Project Director role under the Project Deed.

- Bell Gully provided legal advice about the contractual documentation. We note that the work Bell Gully provided included advice about other issues that were outside the scope of the project management contract.

- PwC (Australia) provided financial modelling.2

3.36

Beca told us that, of the total fees it received for the project, 55% were paid to EPS, 9% to Bell Gully, and 1% to PwC (Australia). Beca retained 35%.

3.37

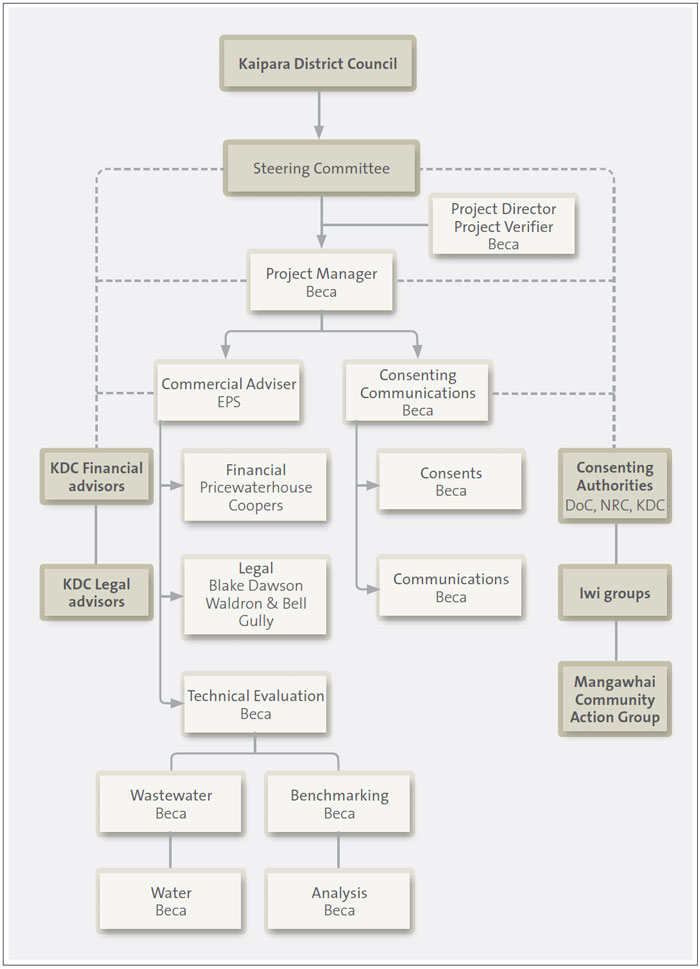

Beca's proposal also included a proposed project management structure for the project, shown in Figure 1. Under this proposed structure, KDC would have its own legal and financial advisers separate to those the consortium provided. There is no record that the Council discussed the fact that it would need to obtain this advice at the Council's meeting on 27 September 2000 or at any other meetings in the early stages of the project.

Figure 1

The proposed project management structure included in Beca's proposal for Project Manager

Source: Beca proposal for Project Manager, Envelope 1, page 10, August 2000.

Project steering team

3.38

The Council agreed at its meeting on 24 May 2000 to establish a project steering team to oversee the implementation of the Plan. At that meeting, the Council decided that the members were to be the project manager (to be appointed), the Deputy Mayor, an individual councillor, the Assets Leader, and both the Mayor and Chief Executive ex officio.

3.39

We could find no formally agreed terms of reference, reporting lines, or delegated decision-making authority for this team. The KDC officer's paper to the 24 May 2000 meeting, which recommended the appointment of members, noted that:

The Project Steering Team will drive the project and will be responsible for continued public consultation. The Project Steering Team will also keep Council involved. Monthly meetings of the Team will be scheduled to ensure timely reporting to Council.

3.40

The team later changed its name to the Project Steering Committee (PSC). Beca told us that it understood that the KDC officer's paper served as the terms of reference for the PSC while it operated. It continued to operate until May 2003. KDC's files did not contain any information to explain why it stopped at that point.

3.41

Beca told us that, initially, the PSC would discuss issues, and then the full Council would make decisions about those issues. After the PSC stopped operating, the usual decision-making process involved EPS preparing a draft presentation, which would be provided to the Chief Executive to review and approve. The presentation would then be made to the Council at a morning workshop, with the acceptance of the draft report and any recommendations later ratified at a Council meeting in the afternoon.

3.42

Beca told us that, in its experience, the process of working through a council subcommittee with the full council making major decisions is normal practice. It considered that the additional process of discussing and debating matters at a Council workshop before the formal meeting should have allowed highly informed decision-making by the Council.

Community Advisory Group

3.43

At its May 2000 meeting, the Council also resolved to call for expressions of interest for people to become members of the Community Advisory Group. At that point, the role of that Group was unclear. However, it appears that its purpose was to keep the community informed and to ensure that information flowed between the community and the PSC. The advisory group, later called the Community Liaison Group, was to include three to five members.

3.44

The PSC appointed the members of the Community Liaison Group. It met from December 2000 until May 2003. Initially, the co-ordinator of the Group was a Beca employee and member of the project team. The other members of the group initially included an iwi representative, four members of the community, and a KDC officer. A ratepayer who was not a resident in Mangawhai, but who owned property there, was appointed shortly afterwards to enable Auckland-based ratepayers to have a contact person.

3.45

In the early stages of the project, during 2001 and 2002, there was regular reporting on the project to the Council. Beca provided monthly reports to the Council, and the Council was also provided with copies of minutes of meetings of the PSC and Community Liaison Group. This practice did not continue for the whole period these groups operated.

The Council's decision to use a public private partnership

What is a public private partnership?

3.46

There is no universally accepted definition of what a PPP is, and the term is used differently in different countries. There are also a variety of PPP structures, which result in different legal relationships and obligations between the private sector partner and public sector partner. In our 2006 report, Achieving public sector outcomes with private sector partners, we defined PPPs as:

A term used in other countries to describe a partnering arrangement where the parties work together for mutual benefit, usually involving private financing… In Australia, the term mainly applies to projects where the private sector partner (usually consortium) makes a financial investment to create or improve an asset, and is responsible for designing, building, maintaining, and operating a facility. The private sector partner receives payments directly from the public sector partner for services provided, and/or income through charges to users.

3.47

The particular type of PPP the Council was interested in is known as a BOOT scheme (standing for Build, Own, Operate, and Transfer). A paper prepared by the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research for Local Government New Zealand in July 1999, Public vs private ownership of utility infrastructure, defines a BOOT scheme as involving the public agency:

…specifying service requirements and pricing structures over a long period, and invited tenders for private operators to submit bids to:

• Design, construct and finance the asset (build)

• Retain ownership of the asset over the designated period

• Operate the asset to provide the service over the designated period, meeting the service standards and working within the indicated pricing structure

• At the end of the designated period, transfer the asset to the public authority at zero or an agreed price.

3.48

Under a BOOT scheme, the private sector partner designs and builds the infrastructure at its own expense. It then owns and operates the infrastructure for some years and charges for its services. The profit it gets from this income covers its construction costs. The result is that the public entity does not need to pay for the infrastructure when it is built. Instead, it simply pays for the services provided by the private sector operator. At the end of the contract period, the infrastructure asset is transferred to the public entity at either no cost or an agreed price. For a public entity with a small income and limited ability to borrow large amounts, this can appear to be an attractive option.

Why the Council was interested in a public private partnership

3.49

We discussed why the Council chose to use a PPP with KDC's former Chief Executive. He told us that the Mayor and several councillors were very keen to use a PPP. The main reason was financial: "It was a way of keeping the debt off the balance sheet." A PPP provided a way for KDC to get the asset built without having to borrow a large amount of money to pay for the construction. With a PPP, the private sector partner also had more room to innovate and carried more of the short-term risks.

3.50

KDC's former Chief Executive also told us that "faced with significant costs for the project Council realised it was not able to fund the project under its current borrowing policies and needed to find a way to deliver the project under Council control but funded off balance sheet". He also noted that the Council was looking to minimise the risk of problems during the commissioning stage of the plant and "looking for innovation from the market".

3.51

The Mayor from that period told us that PPPs were very topical at that time, and there was a benefit for councils in being able to transfer risk to the private sector. The decision to use a BOOT arrangement was largely due to "balance sheet health", which was an issue at the time.

3.52

A review of KDC's files and minutes of meetings showed that the Council considered that the BOOT option was likely to provide long-term cost savings to ratepayers while providing scope for potential bidders to come up with innovative approaches. In line with seeking an innovative approach, the Council agreed, at a workshop facilitated by EPS in February 2001 to discuss risk management for the project, that reuse options and sites would be left flexible to encourage the bidders to identify sites compatible with reuse opportunities. The Council also agreed to try for a 25-year project to provide further scope for innovation. The aim was to maintain a flexible approach to encourage innovative approaches that might exceed the current standards and provide long-term solutions.

How the Council decided to use a public private partnership

3.53

Although the Council asked Beca to provide information about the different options for delivering the project, we and KDC could not find any such information in its files. There was nothing in KDC's files to show that the Council assessed the variety of PPPs that were available, and understood the risks and benefits of each, before deciding to use a BOOT.

3.54

Nor was there any record of a formal Council decision to use a PPP approach to implement the wastewater scheme. However, the minutes of the second Community Liaison Group meeting on 1 February 2001 record the Chief Executive advising that a PPP had been adopted.

3.55

Beca told us that EPS facilitated a workshop with the Council in February 2001 to determine the "Council's preferred risk profile for private sector participation". At that meeting, the Council decided that it did not want to carry:

- the design risk;

- the operational risk;

- the consenting risk (but it recognised that this could be difficult to transfer); and

- the funding risk.

3.56

Beca told us that this risk profile indicated that a BOOT type of delivery method was appropriate, with KDC retaining the responsibility of dealing with ratepayers. KDC would also be required to retain the risk of recovering enough funding to pay the annual tolls to the private sector operator during the contract.

3.57

The notes from that workshop record that its objectives included developing "an understanding of required KDC Management structure for BOOT project (Long Term)". More specifically, the workshop was to determine the allocation of risks between KDC and the private sector partner for the project, the scope of the project to be included in the project brief, and other documents to be put to the market for expressions of interest. By this time, the project was being called the Mangawhai EcoCare project.

3.58

The Statement of Proposal KDC issued in 2003 records that the outcome of the workshop in February 2001 was the preliminary adoption of a BOOT project delivery option.

3.59

However, there was no formal Council resolution to use a BOOT delivery model or the reasons for that decision. Nor were any papers presented to the Council at a Council meeting that discussed the different project models that could be used for the project.

Our comments

Appointing the project manager

3.60

The decision to contract in an expert project manager was reasonable, as was running a tender process to decide who to appoint to the role. However, we regard several aspects of what was done as poor.

3.61

We question the fact that Beca had provided detailed strategic advice to KDC, was engaged to prepare the draft tender documents, and then went on to submit its own tender. Beca told us that this is quite common practice. In our view, it creates a risk that one tenderer will have an advantage over any other bidders from its earlier work on understanding and documenting what the purchaser is seeking. We appreciate that, in some situations, there is no practical alternative. However, in those cases, we expect to see specific steps taken to manage the risk that the process would be regarded as skewed. Although Beca told us that it took steps to manage this risk, we saw no information in KDC's files to suggest that KDC properly identified and managed this risk.

3.62

This problem is compounded by KDC's poor record-keeping. We found no records of the evaluation process, which could have demonstrated that the process was carried out fairly and thoroughly, and that Beca won the tender on its merits.

What to consider before using a public private partnership

3.63

In 2001, there was little New Zealand experience with PPPs and no local guidance on them. However, PPPs were being used in Australia. The Victorian state government established Partnerships Victoria to provide support and guidance on using PPPs to government agencies. Partnerships Victoria published various pieces of guidance on technical issues between 2000 and 2005. It published guidelines on risk allocation and contractual issues (2001) and how to prepare a public sector comparator (2001 and supplementary material in 2003). It published more general policy material in 2003.

3.64

We understand that EPS was familiar with the Partnerships Victoria approach. EPS was involved in Beca's consortium because of its experience with PPPs. We have used this early guidance material from Partnerships Victoria to inform our assessment of what KDC did.

3.65

An overview of the Partnerships Victoria model published in June 2001 identified three core questions for deciding the most appropriate form of delivering a particular public infrastructure service:

- The core services question – that is, whether government should deliver the services.

- The public interest question – that is, whether the project will meet the public interest criteria set in the policy. These criteria include "effectiveness, accountability and transparency, equity, public access, consumer rights, security, privacy, rights of representation and appeal at the planning stages by affected individuals and communities".

- The value for money question – that is, whether the private sector will deliver value for money and how that value can be optimised. This step involves comparing the bids against a public sector comparator (which we discuss further in paragraphs 4.5-4.29).

3.66

The Partnerships Victoria approach applied to the Victorian state government. As a result, it involved various state government agencies, Ministers, and the Treasurer. Figure 2 sets out the major stages in developing a Partnerships Victoria project.

Figure 2

Major stages in developing a Partnerships Victoria project

| Stage | Key tasks |

|---|---|

| The service need |

|

| Option appraisal |

|

| Business case |

|

| Decision: Funding approval | |

| Project development |

|

| Bidding process Decision: Approval to invite Expressions of Interest Decision: Approval to issue a Project Brief |

|

| Project finalisation review |

|

| Final negotiation |

|

| Contract management |

|

Source: adapted from Partnerships Victoria, Guidance Material – June 2001: Overview, page 14.

3.67

As can be seen from Figure 2, the process involves developing a business case for a PPP. In our 2006 report, Achieving public sector outcomes with private sector partners, we summarised much of the emerging good practice guidance on business cases for PPPs. The public entity needs to establish a detailed business case, with financial modelling, to support the decision to go ahead with the project and the preferred procurement method. As part of that business case or before, the public entity should assess different procurement options. The assessed options should include traditional approaches to procurement. The business case should set out a full justification for the chosen procurement option, including how it supports the public entity's vision and strategic plan. The business case should also outline the procurement process, time line, and costs involved. This was not dissimilar to the Partnerships Victoria model set out above.

3.68

Our report explains that the business case should:

- identify clear objectives for the project, including its contribution to the public entity's vision and policy objectives;

- assess the degree of top-level commitment that will be required;

- show that the project and the preferred procurement route are in the public interest;

- assess the likely level of market interest;

- consider the risks of the preferred procurement route;

- show an overview of the structure of the proposed arrangements, including arrangements for governance and accountability, project management, and contract management;

- assess value for money from the preferred procurement route, including a comparison with other procurement options;

- examine funding options;

- consider risk allocation (which will inform the value-for-money assessment);

- examine the affordability and financial implications for the project and preferred procurement route;

- consider legislative compliance;

- consider accounting issues;

- consider the effect on employees;

- identify important stakeholders; and

- identify the main information that the public entity will need to receive throughout the term of the arrangement to effectively carry out its monitoring processes and public accountability obligations.

What the Council considered

3.69

We have not been able to find any evidence that the Council carried out any assessment of the options that were available to it to fund the wastewater scheme. The Council believed that it had only two options to fund the wastewater scheme – debt or a PPP. Despite the early advice it received on its financial situation and options, it did not give equivalent consideration to how it might increase its revenue to pay for the wastewater scheme. This misconception led it to believe that a PPP, where the debt was not on KDC's books, was the only way to deliver the scheme. In short, the belief that the only way to deliver the project was through a PPP was not based on robust evidence or a full consideration of the available options.

3.70

The Council did not carry out a systematic or rigorous consideration of the options before it decided to proceed with a PPP. Because of the limits on its ability to borrow created by its Treasury Management Policy and relatively low income, the Council appeared to take an early view that the only way to fund the wastewater scheme was by using a PPP.

3.71

In our view, the Council should have carefully assessed all the options for funding and delivering the project that were open to it rather than focusing narrowly on using a PPP. Most guidance on PPPs, including that available at the time, emphasises that funding and accounting issues are only a small part of the issues that a business case should address at this stage. They should not be the dominant factor in a decision to use a PPP approach.

3.72

Although there was a lot of discussion about PPPs in New Zealand at that time, they were not being widely used. The Council was therefore deciding to use a project delivery method that was novel in the public sector and that it had no previous experience with. From the information we have been able to find, we do not consider that it paid enough attention to the risks it would need to manage if it followed this approach.

3.73

We note that this decision was also characterised by a lack of clear or formal decision-making and documentation. Important decisions seem to have emerged from ongoing discussions and workshops rather than being formally taken at Council meetings or by people with delegated authority.

Early lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities

3.74

We also saw evidence to suggest that, in these early processes, the Council did not have a clear understanding of the scope of the services that the project managers would provide and therefore lacked an understanding of the role it would need to play in delivering the project. Even with the project managers, KDC would still have its own responsibilities as the ultimate purchaser of the project managers' services and of the scheme. It could not contract out all responsibility to others.

3.75

Beca and KDC entered into a contract for project management services. The contract defined the scope of their respective responsibilities and included a diagram of how the project was to be managed (see Figure 1). That diagram showed that the PSC (which reported to the Council) was responsible for maintaining an overview of the project and for receiving advice from its own professional advisers alongside the advice PwC (Australia) and Bell Gully provided to the commercial adviser.

3.76

In fact, the Council did not set up this system of project governance. The role of the PSC was unclear, and it only operated up until May 2003. In practice, the Council made all decisions on the project through a process of workshops and Council meetings, based on advice directly from the project managers and commercial adviser. No person or group within KDC was charged with monitoring the overall status of the project and its risks. By default, the Chief Executive became personally responsible for this role. The lack of clarity about the roles of KDC, the project managers, and the PSC, and the failure to have a person or group with full oversight of the project, led to significant issues later on. At this early stage, it meant that there was a real risk that issues that were important for the project and KDC would be missed. It also meant that the Council lacked a reliable and routine stream of advice about the project that was independent from the advice it received from its project managers.

3.77

The problems are illustrated by the fact that, in the early stages of the project, KDC did not seek independent legal and financial advice about the project. It did not have a clear understanding of the legal and financial issues that would need to be addressed during the project. Therefore, it did not know whether the project managers would provide advice about those issues or whether it would need its own independent advice. We are unsure whether this was because KDC misunderstood the scope of the services the project managers would provide or whether KDC simply failed to identify the need to do this.

3.78

Although the project management contract set out the limited nature of the legal services to be provided, it appears that KDC officers thought that KDC was going to be provided with all legal services necessary for the project. This misunderstanding was no doubt reinforced when Bell Gully provided (on request) legal advice about issues outside the scope of the services in the project management contract.

3.79

As we set out later in the report, KDC sometimes sought independent legal advice, but this appeared to be on an ad hoc basis. Similarly, Bell Gully provided the additional legal services on an as-required basis and did not provide a systematic overview of the legal issues the project raised.

3.80

In our view, this early work to set up the project created several problems for the future. In simple terms, we conclude that the Council did not fully understand what it was getting into when it embarked on one of New Zealand's first major PPP projects with contracted project managers. In particular, this early lack of a shared understanding about who was responsible for what meant that the Council failed to appreciate that it needed its own direct legal and financial advice about aspects of the project. It also created a risk of legal and financial issues being missed. This risk eventuated several times during the project.

Accountability and record-keeping practices

3.81

The Council's practice of effectively deciding issues in project workshops, based on presentations rather than formal papers, meant that the records did not clearly explain the basis for decisions later confirmed at Council meetings. The minutes alone were often not enough to give a clear picture of what had been decided and why. This lack of information has made it difficult for us to assess how robust the Council's decision-making actually was.

3.82

More generally, we do not support the use of workshops as effective decision-making forums. Workshops can be an extremely useful addition to formal council meeting and decision-making processes, because they enable more open discussion and exchange with advisers. However, the workshops cannot replace considering properly prepared and circulated papers at formal meetings of the Council.

3.83

We are also disappointed that KDC had little or no records to support its procurement activity. Keeping good records that demonstrate the fairness of the process, and how risks were managed, is a basic part of good practice in public sector procurement.

2: PricewaterhouseCoopers in New Zealand told us that it provided advice about only one technical issue. We saw that advice.

page top