Part 4: Using financial statements to understand financial performance

4.1

In this Part, we describe:

- the set of indicators that we have applied to financial data in local authorities' annual reports to better understand financial performance; and

- our analysis of the potential for financial uncertainty and risk in the local authorities.

Why we apply a set of indicators to better understand financial performance

4.2

In our previous reports to Parliament on the results of the annual audits, we began to review the cumulative financial results of all local authorities. Our approach had been to consider the financial data, based mainly on trends, without a method for interpreting, analysing, and assessing the information.

4.3

In our December 2012 report, Matters arising from the 2012-22 local authority long-term plans, we set out our approach to assessing local authorities' financial performance based on financial statements. We based our analysis and observations in that report on historical annual report information and forecast financial information in long-term plans.

4.4

In this report, we continue to seek to better understand financial performance using indicators based on financial information in annual reports. Some of the indicators we have used to assess performance in this report differ from those used in our long-term plan report. This is because some of the items used in the indicators in the long-term plan report were not consistently identifiable in the annual reports of all local authorities.

4.5

As a result of the TAFM amendments to the Act, additional disclosures were required in the 2012-22 long-term plans compared to the 2011/12 and previous annual reports. For example, local authorities were required to separately disclose the amount of capital spending broken down into expenditure to meet additional demand, improve service, and replace existing assets. This was not a requirement in previous long-term plans or the annual reporting against the forecast.

4.6

We have refined our approach to assessing financial performance and interpreting the results, reflecting the discussions we have had with local authorities since the publication of our long-term plan report and as a result of further internal research.

4.7

The set of indicators is not an "audit test". It remains one possible way to better understand a local authority's financial performance and position (and financial sustainability). Financial performance needs to be considered in the broader context and in the light of non-financial performance to provide an overall picture of an entity's performance and position, and overall sustainability.

Our set of financial indicators

4.8

Performance is about achieving objectives in an uncertain environment. It is about striving for something that is attainable but not certain. Therefore, measuring and analysing performance comprehensively requires understanding a local authority's objectives, the risks to achieving those objectives, and the relationship between the two.

4.9

Financial statements are important in assessing performance. Although they say little about many of the non-financial objectives of public entities, they describe and summarise many of the factors that reflect the risk associated with achieving objectives (for example, through the underlying revenue, costs, liabilities, and assets).

4.10

An important part of the usefulness of financial statements is their ability to help a reader understand financial uncertainty in a standardised and comparable way.7 This is a fundamental part of a local authority's performance story.

The potential financial risks in delivering on sector objectives

4.11

Our approach to understanding the financial uncertainty of local authorities is based on our role of providing independent assurance about the performance of public entities to Parliament and the public. We do this through our annual audits of local authorities' financial and non-financial information.

4.12

Risks in the local government sector arise from many different sources, including economic, political, and structural changes inside and outside the local authority. Our approach does not attempt to identify and understand the root cause of risk. Instead, we use the financial statements to help assess the overall effect on three areas that relate to local authorities' financial ability to deliver on their objectives. The three areas are:

- The stability of a local authority's activities (operations, capital, investing, and financing) is about how reliably a public entity plans, budgets, and delivers financial resources. To help understand this component, we focus on financial information that shows how consistent and accurate these activities are (for example, by comparing actual performance with budget/forecast).

- The resilience of a local authority to short-term anticipated events reflects how well it can "bounce back". To help understand this component, we consider financial information that shows how well a local authority can respond without major structural or organisational change. For example, we look at cash flow and income statement items such as interest expense and rates, and balance sheet items such as assets and liabilities.

- The sustainability of a local authority looks at how prepared the entity is for long-term uncertainties and to maintain itself indefinitely. To help understand this component, we consider financial information that indicates how longer-term uncertainties are being managed. We focus, for example, on balance sheet items such as assets, liabilities, and debt, together with related items such as capital expenditure, depreciation, and interest expense.

4.13

To assess the potential risk involved in delivering on sector objectives, we assess, over consecutive financial periods, the relative values, direction, and distribution of various indicators within the three areas discussed above. In other words:

- whether the average values are within a reasonable range and how they are trending over time. This indicates the relative position of the sector's stability, resilience, and sustainability; and

- the distribution of entities that lie outside what we consider "normal" for the sector.

4.14

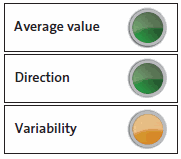

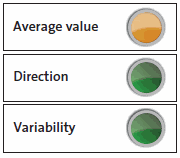

Greater variability implies more uncertainty in the sector's relative position and ability to manage stability, resilience, and sustainability in a standardised and uniform way. We have used a traffic light system to summarise the results of our assessments (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Traffic-light system to summarise the results of our assessments

4.15

Figure 5 provides a visual presentation of our approach. It shows how sustainability builds on the stability and resilience of an organisation, and how we summarise and portray the "normal range" throughout local government by using a standardised measure of variation on either side of the average – in other words, plus or minus one standard deviation.8

4.16

In the rest of this Part, we use the term "norm" to refer to this range of one standard deviation either way from the average for the measure concerned.

Figure 5

Outliers outside standard deviation from average

4.17

To measure the variability among the indicators, we differentiate outliers that lie close to one standard deviation from the average and outliers that are more than two standard deviations from the average. We then analysed these figures collectively.

4.18

As with all analyses of financial performance, there are limitations to what we can infer. Our approach focuses on the potential for uncertainty and does not comprehensively assess local authorities' performance. We are not trying to rank local government entities. Moreover, what is shown as the normal range assumes a regularity that may not always be there. The outliers are not necessarily more uncertain in delivering on their objectives – they may simply warrant further investigation.

4.19

Figure 6 summarises the set of indicators that we have used. Paragraphs 4.20-4.26 explain the information that these indicators reveal.

Figure 6

Our indicators of financial performance

| Stability | Resilience | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| Actual to budgeted net cash flows from operations | Interest expense to rates revenue | Interest expense to debt |

| Actual to budgeted debt | Net cash flows from operations to capital expenditure | Capital expenditure to depreciation |

| Actual to budgeted capital expenditure | Working capital | Gross debt to total assets |

Stability indicators

4.20

For stability, we compare local authorities' actual net cash flows from operations, the debt balance, and the capital expenditure with what was originally budgeted.9 A result of 100% indicates that planning was reliable, budgeting was accurate, and financial resources were used as intended.

Resilience indicators

4.21

The interest expense to rates revenue indicator shows the proportion of rates revenue that is required to service debt. A higher percentage means less flexibility to respond to unexpected events.

|

Clarifying paragraph 4.21: To calculate this indicator, and the interest expense to debt indicator, we have used interest expense as stated on the face of the statement of comprehensive income/income statement. The sector uses different terms to express this item, including finance cost, finance expense, or interest expense. In some instances, interest expense might include finance cost/expense items other than interest relating to borrowing, such as unrealised losses and gains on financial derivatives. |

4.22

The indicator comparing net cash flows from operations with capital expenditure shows the cash surplus available for capital expenditure. A higher percentage indicates a local authority's better ability to pay for capital expenditure using internally generated funds rather than relying on external sources. For inter-generational equity reasons, local authorities typically use debt to fund long-life assets, with costs spread over many years.

4.23

The working capital indicator measures whether a local authority has enough resources to pay what it owes in the next 12 months. A working capital percentage greater than 100 is preferable because that indicates there are more resources available to respond to short-term unexpected events.

Sustainability indicators

4.24

The interest expense to debt indicator shows the effective interest rate of debt. A higher result indicates a relatively higher cost of external funding that the local authority (and therefore the community) has to bear. Local authorities typically use debt to fund long-life assets rather than for business-as-usual operations.

4.25

The capital expenditure to depreciation indicator is used because depreciation is a reasonable estimate of the capital expenditure needed to maintain the asset base.10 A better indicator would have been replacement of assets to depreciation. Local authorities typically call replacement of assets "renewals". Because asset renewals are only part of a local authority's capital expenditure,11 a result above 100% may indicate that the asset base is sustainable. Until 2011/12, local authorities were not required to separately show renewals in their financial statements. This will change from 2012/13 (see paragraph 4.5).

4.26

The proportion of gross debt to total assets indicates a local authority's capability to manage longer-term financial uncertainties. For example, a result of 10% means a local authority has debt equivalent to 10% of assets. This indicator considers debt as a source of funding assets and the influence that external funders may have over the entity.

Detailed analysis using our set of financial indicators

4.27

We used the indicators described in paragraphs 4.20-4.26 to analyse financial information and assess the effect that they have on the three main areas of financial uncertainty. We comment on the local authorities that appear outside the calculated norms.

Stability indicators and trends

4.28

We looked at the actual versus budgeted results for the three years 2009/10, 2010/11, and 2011/12. We have drawn the actual and budgeted results from local authorities' annual reports.

Actual to budgeted net cash flows from operations

Actual to budgeted net cash flows from operations

4.29

The cash flows from operations reflect a local authority's cash surplus (or deficit) from normal, business-as-usual operations.

4.30

The average actual to budgeted net cash flows from operations improved in the three years, from 94% in 2009/10 to 101% in 2011/12.12 The average for the three years was 97%. During the three years, 24% of the local authorities were outliers, and 10% were outside two standard deviations from the average. This indicates low to moderate variability in how accurately local authorities budget net cash flows from operations.13

4.31

We saw three notable outliers:

- Bay of Plenty Regional Council budgeted for negative net cash flows from operations in 2009/10 and 2011/12 but, in those years, achieved positive net cash flows greater than 200% of budget. In 2010/11, the Council achieved only 20% of budgeted positive net cash flows.

- Greater Wellington Regional Council significantly exceeded budget (by at least 163%) in 2009/10, in 2010/11, and in 2011/12. The Council's results reflected the timing of when it received subsidies for its public transport activities.

- In 2009/10, 2010/11, and 2011/12, Environment Southland budgeted consistently for negative cash flows from operations but had positive cash flows.

4.32

Based on reviewing their annual report, it was difficult to work out the reason for the results of Bay of Plenty Regional Council and Environment Southland, including why they had budgeted for negative net cash flows from operations. This raises questions about the accuracy of their cash flow budgets – typically, public entities do not budget for negative net cash from operations. Negative net cash from operations suggests cash is required from external funding sources, such as debt, for day-to-day operations.

4.33

This was not uncommon - many local authorities' (and other public entities') annual reports do not effectively explain significant variances to budget for items in the cash flow statement. Local authorities typically explained significant variances identified in the income statement and balance sheet. We commend Tauranga City Council's 2011/12 annual report disclosures because they explain why there were large differences from budget and the previous year.14

Actual to budgeted debt

Actual to budgeted debt

4.34

The accuracy with which local authorities forecast their debt requirements improved during the three years, from 70% to 81%. The average actual to budgeted debt for the three years was 76%, which suggests that the budgeting accuracy could further improve. A quarter of the results were outliers, including 2% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This shows that there was little variability in how accurately debt was budgeted.

4.35

The forecasting of debt is closely associated with capital expenditure. For actual to budgeted capital expenditure, local authorities achieved 80% of their budget during the last three years (see paragraph 4.37).

4.36

Eight local authorities had no debt as at 30 June 2012. Another five local authorities had debt balances less than $1 million. Most of these 13 local authorities are regional councils. As a result, more outliers were below one standard deviation than above.

Actual to budgeted capital expenditure

4.37

The accuracy with which local authorities forecast capital expenditure improved during the three years, from 76% to 85%. The average actual to budgeted capital expenditure for the three financial years was 80%. Twenty percent of the local authorities were outliers, including 6% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This shows low to moderate variability with the accuracy of actual to budgeted capital expenditure.

4.38

We noted that Environment Southland spent consistently more on capital expenditure than budgeted. The amount budgeted was typically less than $1 million a year (from a low base) but the local authority had more capital expenditure each year - up as much as 194% in 2011/12. In its annual reports, Environment Southland disclosed that the variances reflected spending on an integrated regional information system (some of which had been budgeted as operational expenditure) and an upgrade to the financial management system.

4.39

Some local authorities had less capital expenditure than budgeted but we did not see any that consistently spent less than the average during the three years.

Summary observations about stability

4.40

Overall, in the last three years, local authorities were more accurate in budgeting their net cash flows from operations, debt level, and capital expenditure. Average results for all three indicators vary between 75% and 96%. The improving results during the last three years are evidence that local authorities are getting better at forecasting.

4.41

The relationship between the three indicators of actual to budget net cash flows from operations, debt levels, and capital expenditure are linked and important to understanding the actual funding position that local authorities seek to achieve. We expect there to be annual variations in local authorities' actual to budget results, although explanations of the variations was not always obvious from the annual reports.

4.42

We have raised with the sector, on a number of occasions, the need for clarity about these key decisions – particularly decisions about the level of capital expenditure achieved (which is not necessarily unrelated to the cash and debt required). General reasons we have been given include:

- efficiencies obtained in the procurement of actual capital projects;

- deferrals of capital expenditure because of other events (for example, a flood event drawing on cash funds available);

- changed priorities; and

- financial pressures.

4.43

In our view, explanations like this should be more transparent in the annual report because they are critical to understanding why actual to budgeted variances are occurring. There is an opportunity to address this in future annual reports.

|

Amendment to paragraph 4.43: The last three lines of this paragraph were not as clear as they could have been, so we have deleted them. |

Resilience indicators and trends

4.44

We looked at three indicators of resilience that consider how well local authorities can respond to short-term shocks. For the interest expense to rates revenue indicator we considered results for two years – 2010/11 and 2011/12. We did not readily have available the interest expense information from the 2008/09 to 2009/10 annual reports. For net operating cash flows to capital expenditure and working capital indicators, we considered results for four years, 2008/09 to 2011/12.

Interest expense to rates revenue

4.45

This comparison looks at the proportion of rates revenue used to service debt. A high percentage means less flexibility to respond to unexpected events.

4.46

The average interest expense to rates revenue was 7.8%. We reported that the average in the long-term plans was 9%. Thirty-two percent of the results were outliers, including 4% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. Although this indicates low variability, the result is affected by some local authorities with no debt – they did not incur any interest expense. On the other hand, there are some local authorities that have high debt balances and a high proportion of rates revenue is used to cover the interest expense. These local authorities have greater potential or risk of not being able to respond to short-term events compared to other local authorities.

4.47

We saw the following notable outliers:

- Kaipara District Council had interest expense to rates revenue of 23% in 2010/11 and 35% in 2011/12. Kaipara District Council's largest infrastructure project is the Mangawhai Community Wastewater Scheme.

- Tauranga City Council had interest expense to rates revenue of 26% in 2010/11 and 2011/12. Tauranga City Council's debt has increased each year for the last three years, reflecting its borrowing to fund capital projects.

- Western Bay of Plenty District Council had interest expense to rates revenue of 37% in 2010/11 and 32% in 2011/12. Western Bay of Plenty District Council's debt has increased each year for the last three years, reflecting its borrowing to fund capital projects.

Note: See Western Bay of Plenty District Council, Annual Report 2011/12, page 89, 4(a) Finance income and finance costs.

Net cash flows from operations to capital expenditure

4.48

This comparison looks at the local authority's cash surplus (or deficit) from normal business-as-usual operations that has been or could be used towards capital expenditure requirements. Apart from cash surplus from normal operations, a local authority can fund capital expenditure by selling investments or assets or borrowing to pay for the long-life assets. A higher percentage indicates that the local authority is funding capital expenditure with internally generated funds rather than external funding (debt).

4.49

The average net cash flow from operations to capital expenditure was 81% in the last four financial years. The average percentage in each of the four years fluctuated between 70% and 87% - there was no consistent pattern. Nine percent of the local authorities were outliers, including 4% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This indicates low variability. There were as many outliers above as below the average.

4.50

We did not see any local authorities that were consistently outliers. Although an average of 81% is not an unwarranted position to be in, if the percentage decreases over the longer term, it means a local authority is relying more on external funding.

Working capital

4.51

This indicator compares current assets to current liabilities. It measures whether a local authority has enough resources to pay what it owes in the next 12 months without having to resort to other options, such as borrowing further or selling long-term investments and assets.

4.52

The average working capital result was 187%. Twelve percent of local authorities were outliers, including 6% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This indicates low to moderate variability. In general, regional councils have higher working capital percentages than territorial local authorities. This is because territorial authorities typically have some debt reflected in current liabilities. Debt is classified as a current liability if it is due for repayment in the next 12 months. Local authorities typically have arrangements where this debt is reissued but under different borrowing terms and conditions. This can have a significant effect on this indicator but does not reflect an immediate cash need for the local authority.

4.53

Bay of Plenty Regional Council, Environment Southland, Hawke's Bay Regional Council, Mackenzie District Council, Napier City Council, Otago Regional Council, and Wairoa District Council were consistent outliers during the four years, with working capital results greater than 200%. On the other hand, we noted that 23 local authorities (30%) had working capital results less than 100%.

4.54

Our analysis looked at working capital at a point in time. We acknowledge that some local authorities manage their working capital and cash requirements very closely during the year to reflect when cash is required. For example, it is more cost-effective to draw on cash facilities when required because investment returns are always lower than the cost of borrowing.

4.55

We also note that a very high working capital result does not always reflect good working capital management. A high working capital result could mean that a local authority is not managing its cash resources effectively by, for example, paying off debt rather than holding cash as an investment.

4.56

The 23 local authorities with a working capital result less than 100% had greater potential for uncertainty with responding to uncertain events compared to other local authorities. We acknowledged earlier that there could be a significant level of debt included in current liabilities that could be reissued but subject to different credit terms and conditions.

Summary observations about resilience

4.57

In general, local authorities were in a good position with interest expense to rates revenue and working capital. The average value with net cash flows from operations to capital expenditure could be better than the current 81% because it means that 19% of capital expenditure is paid for from other sources, most likely debt. However, it could be appropriate, particularly for local authorities experiencing high growth, to spread the cost of capital expenditure over many years, in line with principle of inter-generational equity.

4.58

There was little variability in the results for interest expense to rates revenue and net operating cash flows to capital expenditure, but moderate variability with working capital. Thirty percent of local authorities had a working capital result of less than 100%, which means that these local authorities could have faced greater risk than other local authorities in their ability to respond to unexpected events through working capital management.

Sustainability indicators and trends

4.59

We looked at three indicators of sustainability that consider how durable a local authority is in the face of longer-term uncertainties. For interest expense to debt, we considered results for two years only – 2010/11 and 2011/12. For capital expenditure to depreciation and gross debt to total assets, we analysed the results for four years – 2008/09 to 2011/12.

Interest expense to debt

4.60

The interest expense to debt reflects the cost of borrowing – the effective interest rate.

4.61

The average effective interest rate during the two years was 6.49%. In our long-term plan report, local authorities forecast an average interest rate of 5.9% during the 10 years to 2021/22. Seventeen percent of the local authorities were outliers, including 3% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This indicates relatively little variability between local authorities.

4.62

Because we analysed only two years' of results, we cannot draw clear conclusions. However, we have taken into account the forecast average interest rates analysed in our long-term plan report. We concluded that the average interest rate was reasonable, given the current and forecast market interest rates.

4.63

In our long-term plan report, we listed 18 local authorities that were shareholders of the Local Government Financing Agency (LGFA). At the time of writing, another 12 local authorities had joined as shareholders. A further six local authorities have joined LGFA as borrowers and guarantors. This means that 36 local authorities have access to the funding arrangements of the LGFA – potentially lower interest rates and the ability to borrow in foreign currency. We calculated that the debt balance of those 36 local authorities was $8.1 billion and represented 91% of the total debt of local government as at 30 June 2012.

4.64

We have not looked in detail at whether the 36 local authorities access none, some, or all of their borrowing through the LGFA.

Capital expenditure to depreciation

4.65

The capital expenditure to depreciation indicator reflects the reinvestment to maintain or improve the assets' performance capability and the nature of the service that the assets provide. We analysed renewals expenditure to depreciation in our long-term plan report because this indicator provides a better picture of assets' sustainability. However, we were unable to look at renewals to depreciation because local authorities were not required to disclose renewals in annual reports before the TAFM amendments to the Act.

4.66

The average capital expenditure to depreciation was 173%. Sixteen percent of results were outliers, including 4% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This indicates low variability among local authorities. We saw no clear trend, because the average percentage for all local authorities fluctuated during the four years. In our long-term plan report, we reported that the average forecast was 135% during the 10 years to 2021/22.

4.67

Most local authorities had capital expenditure greater than 100% of depreciation. Fast-growing local authorities typically had a higher percentage than others. The capital expenditure should reflect that set out in the asset management plans. As discussed in paragraph 4.37, local authorities tended to carry out less capital works than budgeted.

4.68

Three local authorities consistently had a capital expenditure to depreciation result less than 100% in each of the four years from 2008/09 to 2011/12. The results ranged as follows: Hutt City Council was 62% to 86%; Waimate District Council was 63% to 99%; and Kawerau District Council was the lowest overall, with 44% to 59%.

4.69

A consistently low percentage could call into question the ability to maintain assets in the long term or suggest a need for a significant rise in capital expenditure in the future. This result warrants further research. To fully understand whether this result indicates a future issue requires sound and comprehensive knowledge of the state and performance of the individual local authority's infrastructure systems. The requirement to split capital expenditure into three categories from 2012/13 onwards will also help in interpreting future results for this indicator.

Gross debt to total assets

4.70

For the gross debt to total assets indicator, a value higher than 100% indicates that a local authority has more debt than assets. This is highly unlikely in local government because local authorities have a large and long-life asset base.

4.71

The average gross debt to total assets was 4.5%. Forty percent of local authorities were outliers, including 5% that were outside two standard deviations from the average. This indicates a moderate to high variability. We saw no clear trend - the average percentage for all local authorities fluctuated during the four years. In the long-term plan report, we stated that the average gross debt to total assets forecast in the 10 years to 2022 was 6%, so the current average is comparable to that forecast for the coming years.

4.72

Seven local authorities Central Otago District Council, Environment Southland, Mackenzie District Council, Northland Regional Council, Taranaki Regional Council, Waikato Regional Council, and Wairoa District Council had no debt in any of the four financial years.

Summary observations about sustainability

4.73

In general, local authorities' interest rate, capital expenditure to depreciation, and gross debt to total asset indicators are within a reasonable range. However, the distribution of results for the latter two indicators during the last four years make it difficult to see any pattern of direction and reflects the varying circumstances of local authorities.

4.74

Variability with the gross debt to total assets indicator was moderate to high. Seven local authorities did not have any debt in each of the last four financial years which contributed to the assessment of variability. Overall, the gross debt to total assets percentage is relatively low, so there is less cause for concern.

Our conclusions about using financial statements to understand financial performance

4.75

Overall, our finding on the potential short-, medium-, and long-term risks with local authorities delivering on their objectives is mixed.

4.76

Positively, local authorities are showing improvements in their capability to plan, budget, and deliver the financial resources required to meet their service delivery objectives. Operationally, the local government sector remains strong in this aspect. Debt levels have remained within a reasonable range. Local authorities' ability to service that debt is also strong and consistent throughout the sector. The indicators of long-term sustainability are all within a reasonable range, implying some robustness in the capability to manage longer-term uncertainties.

4.77

In our long-term plan report, we signalled local authorities' intention to live within their means and that they are not raising rates to unreasonable levels to do so. We continue to hold that view. Continuing analysis of actual against budgeted spending will allow for this insight into the strength of local authorities' financial performance.

4.78

In the last four years, there has been a pattern of ongoing under-investment of capital expenditure and (related) debt requirements. The direction of many of the indicators of resilience and sustainability suggest some variability and warrants further analysis. There are more outliers than we would have expected for many of the indicators. This was particularly so for short-term planning and budgeting across local authorities for capital investment and funding. This variability in part reflects the variety of approaches to managing these potential short-, medium-, and longer-term risks.

4.79

Our analysis of local authorities' 2012-22 long-term plans showed that the main area of risk related to local authorities' ability to ensure sustainability in the longer-term. This was based on what appeared to be declining capital investment towards 2021/22 and ongoing issues in forecasting capital and funding needs.

4.80

In the last four years, internally generated funds were less than the sector's capital expenditure needs. Consequently, for some local authorities, the level of debt was increasing. This was, in part, due to some local authorities providing for anticipated growth and also adhering to the statutory principle of inter-generational equity, which supports a level of debt funding of services using infrastructure assets. These local authorities will need to actively monitor capital investment needs to ensure that debt funding is manageable despite the reasonable debt levels at present.

4.81

We recommend that more work be done to understand the nature of the potential risks that local authorities might be exposed to in the short to medium term, and how they are planning to respond to those risks.

4.82

We plan to continue to assess local authorities' financial performance through a set of indicators. The comparison of actual performance against that budgeted continues to add valuable insight to the financial performance and risks in the sector.

7: The terms "risk" and "uncertainty" can have different meanings. For simplicity, we use the terms interchangeably to mean the potential for variation from what is expected or considered "normal". For instance, a public sector entity's large operating surplus can be as much an indicator of uncertainty (or risk) as if it had a large operating deficit.

8: Standard deviation is a statistical measure of how far the data points are spread. A small standard deviation indicates that the data points tend to be close to the average. A large standard deviation indicates that the data points tend to be further from the average.

9: Capital expenditure is expenditure on property, plant, equipment, and intangible assets.

10: Depreciation reflects the depreciation expense from property, plant, and equipment, and amortisation expense from intangible assets.

11: The other categories of capital expenditure are to improve the levels of service, and assets to meet additional demand.

12: We made some adjustments to the raw percentage results, including capping results at 200%.

13: A sustained or consistent result of 100% indicates reliable planning, accurate budgeting, and robust delivery. A result below 100% means that the local authority achieved less than it had budgeted, and a result higher than 100% means that the local authority exceeded budget (for example, 120% means exceeding budget by 20%).

14: See Tauranga City Council, Annual Report 2011/12, pages 223-228.

page top