Part 6: Delivering core services through substantive council-controlled organisations

The formal structure and the intentions of the Auckland reforms

6.1

A CCO is an organisation in which a council controls 50% or more of the votes or has the right to appoint 50% (or more) of directors or trustees.

6.2

A substantive CCO is unique to Auckland and is established under the Local Government (Tamaki Makaurau) Reorganisation Act 2009 or the Local Government (Auckland Council) Act 2009. A substantive CCO is a CCO that is responsible for delivering a significant service or activity on behalf of the Council, or that owns or manages assets with a value of more than $10 million.

6.3

The Auckland Council is operating under a new model where substantive CCOs deliver services and activities that are funded by more than 35% of the Council's total rates. These CCOs also manage $25 billion of assets owned for the benefit of the public, which makes up 70% of the Council's consolidated total assets. The Council's CCOs provide many of the services that usually form the core activities of local authorities in New Zealand. These services include roading and public transport, water and waste water, and economic development activities.

6.4

The Council has seven substantive CCOs:

- Auckland Council Investments Limited;

- Auckland Council Property Limited;

- Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development Limited;

- Auckland Transport;

- Auckland Waterfront Development Agency Limited;

- Regional Facilities Auckland; and

- Watercare Services Limited.

6.5

Figure 5 shows the structure of the Council's substantive CCOs.

Figure 5

Structure of Auckland Council's substantive council-controlled organisations

Source: Adapted from Auckland Transition Agency (March 2011), Auckland In Transition: report of the Auckland Transition Agency, page 117, Figure 4-1.

6.6

The Council also has several CCOs that existed under the former councils and continue to operate. We do not discuss these CCOs in this Part, which focuses on the Council's substantive CCOs.

6.7

Although each substantive CCO has its own specific objectives, the Local Government Act 2002 identifies the principal objective of all CCOs. In summary, this principal objective is to:

- achieve the objectives of its shareholders, both commercial and non-commercial, as specified in the statement of intent (SOI);

- be a good employer;

- show a sense of social and environmental responsibility by having regard to the interests of the community in which it operates and by endeavouring to accommodate or encourage those interests when able to do so; and

- if the CCO is a trading operation, to conduct its affairs in keeping with sound business practice.

6.8

The general governance framework is set out in legislation. The essential elements of the framework are:

- The Council owns the CCOs. It appoints directors to govern each CCO.

- CCO directors are accountable to the Council for the governance of the CCO. They must consult the Council on their draft SOI and report half-yearly to the Council on their operations.

6.9

Substantive CCOs must also:

- "give effect to" the relevant aspects of the Council's LTP, and "act consistently" with any other plan of the Council "to the extent specified in writing by the governing body of Council"; and

- consult the Council on draft asset management and funding plans.

6.10

The benefits of delivering activities through CCOs are commonly identified as:

- improved commercial focus – that is, operating a company with a professional board of directors with the objective of achieving greater operating efficiency;

- introducing, through board appointments, commercial disciplines and specialist expertise to add value to CCOs and help them to better achieve their objectives and the Council's long-term strategies; and

- focusing on achieving a constrained set of business objectives, bringing a unifying focus to the organisation along with efficiencies through a corresponding drive to align resources with the required outcomes.15

6.11

The ATA identified the primary public concern about the use of CCOs as a possible loss of public transparency.16 However, CCOs are subject to the access-to-information provisions of the Local Government (Official Information and Meetings) Act 1968. In addition, two of all Auckland's CCO meetings each year must be open to members of the public (including allowing time for members of the public to address the meeting) when consideration is being given to the CCO's:

- draft SOI; and

- performance during the previous financial year.

6.12

The Royal Commission proposed rationalising the former councils' more than 40 CCOs. In doing so, the Royal Commission said that:

For the Auckland Council to plan and deliver the infrastructure and services to meet its requirements, it will need access to the best commercial and engineering expertise and resources. CCO structures and boards of directors can bring these required skills and expertise.17

6.13

The ATA saw CCOs as a way of ensuring efficient management of operations, allowing the Council to focus on developing policies, strategies, and plans to drive Auckland forward.18

What we heard – CCOs are achieving the focus sought, but tension is inherent and the Council's formal expectations are increasing

6.14

Most people we spoke to saw the resulting CCO structure as a good model. It was useful for each CCO to have its own areas of focus and a board that brings relevant expertise to that focus. CCOs have allowed many core services to continue seamlessly, or even have their efficiency and effectiveness enhanced, during the transition to the new Council.

6.15

Concentrating all transport activity in one organisation has made it easier to give perspective and context for transport work and to align transport activities. Having fewer Council decision-making bodies to negotiate with, for matters such as funding shares, has also helped decision-making to proceed more easily. This concentration has enabled work on significant new transport projects to begin – for example, the Auckland Manukau Eastern Transport Initiative.

6.16

Having a single Auckland Transport organisation has also enabled a joint traffic operations centre to be set up with the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA). We were told that Auckland Transport and NZTA sharing their resources to operate traffic systems throughout the Auckland region is saving tens of millions of dollars. These savings come from the wider economic benefit of traffic moving more efficiently and smoothly on the existing roads.

6.17

There have also been achievements for other CCOs:

- Watercare recently reported that it had achieved regional cost efficiencies against those forecast of $104 million, and reduced the forecast retail price of drinking water by 15%. Wastewater price increases have also been held to levels lower than that forecast by the former councils.

- Auckland Council Property Limited had been able to complete the consolidation of the former councils' commercial and non-core property holdings.

6.18

Some people we spoke to questioned whether the current number and purposes of the CCOs are right. The Council has identified several areas where there is duplication of, or lack of clarity about, specific functions.

6.19

For example, three CCOs and the Council have intersecting interests in services and activities at Auckland's waterfront. This has led to work to clarify the CCOs' and the Council's respective roles, raising questions about the future ownership and maintenance of public infrastructure on the waterfront, Waterfront Auckland's role in delivering major events in the waterfront precinct, and whether commercial returns can be used to fund public infrastructure and non-commercial activities.

6.20

Other examples include:

- the extent of Regional Facilities Auckland's involvement in developing facilities and sectors;

- both Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development Ltd and the Council having economic development functions; and

- both Auckland Transport and the Council having strategy functions, with Auckland Transport needing the transport implications of the Council's strategies and plans to be co-ordinated.

6.21

Many people perceived that Council elected members and senior officers are held accountable for decisions of CCOs, and expressed concern about Council's ability to maintain alignment in CCO service delivery with its plans and strategies. The Council intends to carry out a full review of CCOs after the next local body elections. In our discussions with people from the Council, many told us that they expected there would be changes to CCO arrangements after this review.

Governance arrangements set up by the Auckland Council

6.22

The governing body of the Council has set up the following institutional arrangements:

- The Accountability and Performance Committee is responsible for monitoring the performance of CCOs, and approving policies relevant to CCO accountability.

- The CCO Strategy Review Sub-committee, chaired by the Mayor, is a sub-committee of the Accountability and Performance Committee. It is responsible for appointing CCO directors and negotiating CCOs' SOIs, which the CCOs report against.

- There are bimonthly meetings between the Mayor and the Chairperson and Chief Executive of each CCO.

6.23

The CCO Governance and Monitoring Department, a dedicated team within the Council's Finance Team, provides advice and monitoring on matters such as strategy, governance, and board appointments. This team has established strong governance relationships with its CCOs. The CCOs' SOIs for 2012-15 have recently been completed, and a range of policies are in place. The Finance Team carries out other financial planning, monitoring, and reporting, and Council functional technical experts provide advice as required.

6.24

The Council has put extensive effort into formal structured arrangements for CCO governance. Clearly stated and communicated performance and accountability expectations are intended to help ensure that CCO boards understand what the Council expects of CCOs. A degree of tension about who should control certain types of decisions is seen as inevitable. However, Council staff seek to minimise this tension by getting both parties to have clear understandings and expectations of each other.

6.25

The expectations of the Council are set out in the CCO accountability policy, the Mayor's annual letter of expectations, and the Guide for Council-Controlled Organisations.

6.26

The CCO accountability policy outlines the Council's expectations of its substantive CCOs. The policy, which is required by legislation, identifies CCOs as partners in the delivery of the Council's objectives and priorities, with a key role to play in the Council's vision for Auckland. The Council expects each CCO to align its activities with those of the Council and to act consistently with its vision and with the objectives set for it by legislation.

6.27

The Mayor's annual letter of expectations is intended to guide the CCOs' strategic direction and help them prepare their SOIs. The letter of expectations sets out the parts of the draft Auckland Plan that each CCO is expected to contribute to, priorities in the draft LTP that each CCO is required to give effect to, and local community priorities and preferences identified in local board plans that each CCO is to consider addressing when preparing its SOI. Officers of CCOs we spoke to were comfortable that they understood and could make progress with the Council's expectations for delivery initiatives toward the Auckland Plan and LTP.

6.28

The Guide for Council-Controlled Organisations outlines the Council's expectations of the boards of CCOs. It is designed to help boards to operate efficiently in their roles and to clarify their responsibilities. The guide outlines the minimum requirements expected by the Council for CCOs, with the SOI incorporating additional obligations. The guide is intended to complement the letters of expectation sent by the Mayor at the start of the annual business planning round. The guide sets out the Council's expectations for roles and responsibilities, expectations and key relationships, financial governance, and board governance.

6.29

Council governors and staff we spoke to considered that their appointed CCO board members generally understood Auckland's CCOs to have been based on a very commercial, arm's-length model, similar to State-owned enterprise boards. However, their view was that a State-owned enterprise model was not appropriate for Auckland's CCOs, and acknowledged that board members' expectations had probably been disappointed in this regard.

6.30

In their view, Crown entities were a more relevant central government parallel to Council's substantive CCOs. They noted that legislation has made Auckland's CCOs responsible for public good and community services to a much greater extent than anywhere else in New Zealand local government. CCOs deliver services and activities that are funded by rates, and manage assets owned by the Council for the benefit of the public. The Council also provides financial backing for much of the CCOs' capital expenditure.

6.31

The Shareholder Expectation Guide for Council Controlled Organisations says the Council expects to hold CCOs:

… accountable for the efficient and effective use of funding from all sources, and for the management of assets identifying two high level funding principles:

1. The role of the council is to prioritise funding for competing needs and purposes across the region, and to hold CCOs accountable for the wise use of public funding.

2. Boards must be empowered with sufficient flexibility to determine the best allocation of funding to meet required levels of service.19

6.32

The Shareholder Expectation Guide acknowledges the inherent tension between the two principles. It concludes that, where there is conflict, the first principle must prevail.

6.33

Some staff said they were not sure why the Royal Commission chose the CCO model for the Council. The Council has sought to understand the roles and responsibilities of CCO boards. It has also sought to clarify what kind of relationship with the Council would be most appropriate for each CCO, using central government's governance of subsidiary entities as a model. The Shareholder Expectation Guide uses a purpose-based continuum to assess how much empowerment a CCO may need to deliver services for the Council efficiently.

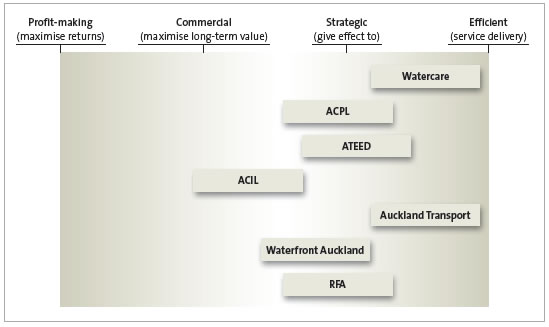

6.34

Figure 6 sets out this continuum. On this continuum, the Guide suggests that CCOs with strategic or commercial purposes will struggle to "add value" for the Council without empowerment. On the other end of the continuum, the Council may need to use its powers to require CCOs with service delivery purposes to act consistently with the Council's plans and strategies. For service delivery purposes, Councils may also expect greater interaction for planning and under the "no surprises" policy.

6.35

We heard that the Council's expectations of CCOs were understood and that there was satisfaction with the amount of empowerment available to the more commercially oriented CCOs. However, there was significant comment made about relationship difficulties and tensions for Auckland Transport and Watercare Services, which are the two CCOs identified as closest to service delivery.

Figure 6

Purpose of Auckland Council's substantive council-controlled organisations

Source: Adapted from Auckland Council (2012), Shareholder Expectation Guide for Council Controlled Organisations, page 7.

6.36

Auckland Transport and Watercare Services are the CCOs that provide services that are traditionally core services delivered by local authorities. For Auckland Transport, central government is also an important stakeholder in its activities, with about 35% of Auckland Transport's $755 million revenue coming from the NZTA and 43% from the Council. Watercare Services receives no funding from the Council. From 1 July 2012, Watercare Services began charging for its water and waste services through water meters.

6.37

Legislation suggests that a closer relationship between Auckland Transport and the Council is required than for the other substantive CCOs. For example, Auckland Transport is also the only CCO where an elected member of the governing body is permitted to be appointed as a director.

Discharging the Council's governance role, and securing CCO alignment and integration

6.38

Although tension was clearly growing, all CCOs remained committed to constructive progress in their governance relationships with the Council. Some people we spoke to mentioned that the waterfront and traffic control events on the Rugby World Cup opening night were a defining moment when the Council recognised that CCO structures could not prevent the Council from being held politically responsible. They attribute these events with a perceived change to a more controlling and formal approach in the Council's relationships with CCOs.

6.39

The Shareholder Expectation Guide was pointed to as an example of this more controlling approach. The guide ranges from high-level expectations that define the CCOs' relationship with the Council and the behaviour required of a public entity (such as the "no surprises" policy, transparency, and fiscal prudence) to setting out detailed expectations about more operational matters.

6.40

Some people we spoke to said that some of these detailed expectations are overly specific and not consistent with a strategic governance relationship. Examples include:

- All CCOs are required to use the Council's "pohutukawa logo" in all their communication, marketing, and advertising.

- The Council requires budgeting and financial reporting at a "sub-activity" level. The Shareholder Expectation Guide describes this as groups of outputs, but some people we spoke to described it as project-by-project. As well as output budgeting, CCOs are expected to get the governing body's agreement to move funds between outputs. CCOs are also expected to return any surpluses or unspent funding at year-end to the Council. From the Council's perspective, these processes enable overall management of the Council's financial operations. However, some CCO officers we spoke to considered that these processes did not fit the regional and long-term planning needs of long-lived assets – for example, transport and water service assets.

- Decisions about new projects, re-allocation of funding, and business decisions (for example, appointment to subsidiaries and pricing decisions) all need to be made with the Council's approval or within the Council's guidance, and plans and strategies.

- Communication and liaison protocols set unnecessarily onerous demands. These included activities such as daily meetings between the Council and CCO communications staff, requirements for CCOs to advise the Council of submissions they intend making in response to calls from external agencies, and informing the Council of any activities requiring engagement with central government.

6.41

For none of these expectations are the Council and CCOs in disagreement about the principles of good governance relationships. Rather, the issue for people from CCOs that we spoke to was about the extent to which a CCO should be empowered to determine how best to respond. Records of discussions between the governing body and CCO board members conclude that there is enough formal performance monitoring between the Council and CCOs. More interaction was sought between CCO board members and councillors to foster a culture of co-operation and trust that is oriented towards the future, and that enables CCO governors and staff to understand the effect of CCOs' business decisions for the Council.

6.42

For their part, Council staff told us that monitoring performance measures and targets is easy – after the fact. Their greater difficulty was with integrating and aligning planning and future initiatives. CCO boards were sometimes viewed as a barrier to the Council's strategy and planning, by not refining their leadership of the CCO for the new arrangements and changing circumstances.

6.43

The Council appeared to be taking other steps to secure this alignment and integration, in addition to the Shareholder Expectations Guide. In particular, we were told that the Council is currently amending CCO constitutions so that the Chief Executive of the Council can be appointed as a member to any board. This would be a reserve power to help with aligning mission and strategy if necessary.

Planning and budget processes

6.44

Aligning the preparation of the Council's LTP with each CCO's SOI so that they are complete and consistent with each other is complex. These matters are works in progress, with both the Council and the CCOs identifying aspects they would like to improve in future.

6.45

The process for the governing body to provide comment on CCO's SOIs took more than six months. Feedback was provided as three separate sets – from local boards, from the IMSB, and from Council staff. Several CCOs considered that their SOI had become too operationally and delivery focused as a result, with too many expectations and measures. They would have preferred their SOI to clearly focus on setting the basis for assessing the CCO's success from the standpoint of the Council's accountability policy and its expectations as a shareholder.

6.46

We also heard that Council staff had found it difficult to get information from CCOs in the templates or time frames required for preparation of the LTP. There have not been similar issues for those CCOs that receive financial services from the Council. The CCOs that were perceived to be unhelpful in providing information said they were surprised and dismayed when Council staff raised these issues. The issues were attributed to miscommunication and misunderstanding of the overall financial model the Council was constructing, leading to information being supplied in a different way to that sought.

Governing body relationships

6.47

Many of the issues that were raised with us in our discussions about CCO governance were about articulating and formalising expectations and the flow of information for planning and reporting purposes.

6.48

As well as the Council's formal arrangements for interacting with CCOs, the Mayor, the Chairperson of the Accountability and Performance Committee, and the Chief Executive meet quarterly with the Chairpersons of CCOs. There is frequent information interaction between CCO senior officers and the Mayoral Office depending on the public effect of the CCO's services and which issues are of public interest.

6.49

We were told that the CCOs are very responsive to the needs of the Mayor and governing body. However, they are seen as less responsive to Council staff. For example, we were told that CCOs could be slow to provide information on the grounds that it needs to be discussed by the CCO board first. Council staff were concerned that, as a result, governing body and local board members were frequently surprised by late information about matters such as project and budget changes.

6.50

Similar to views on how the governing body and local boards take local and regional perspectives into account in decision-making, some people we spoke to described tensions between CCOs and local boards in attempting to reconcile project and timing priorities within financial constraints.

6.51

The Council has asked CCOs to make a greater commitment of effort and resource to local boards – for example, by dedicating staff to attend meetings. In practice, the extent of involvement that local boards seek from each CCO varies according to the issues of the day, the interests of each local board, and the activities of the CCO.

6.52

Tensions are arising for individual boards and on specific issues, given the different areas of focus for local boards and CCOs. As it is for the Council, servicing 21 local boards is a logistical and resource challenge for CCOs. Despite this tension, local boards and CCOs understand that significant decisions about service needs and expectations need to be informed by community views and technical advice.

Our observations – strong and appropriate governance arrangements are important

6.53

In a letter to the Chief Executives of the Council and Watercare Services in August 2011, the Auditor-General noted that it is important that the Council has strong and appropriate governance arrangements for its CCOs. She noted, in particular, that the substantive CCOs are central to the well-being of Auckland and that the Council is politically responsible for their activities. She advised that she expected a framework for governance and accountability that:

- reflects the importance of CCOs to Auckland and to the Council;

- enables governing body members to pursue their political interest in CCOs' business openly and transparently;

- offers opportunity for genuine engagement between the Council and the CCOs, at appropriate intervals and at the appropriate level of seniority, on the Council's strategy and priorities and on the CCOs' business performance and risks;

- enables adequate consideration of CCOs' draft SOI and draft asset management and funding plans;

- complies with the relevant legislation; and

- does not impose a "compliance burden".20

6.54

The letter identified two main risks for the Council from its current effort to develop more formal governance reporting and monitoring frameworks:

- that a CCO's independence from the Council is threatened or circumscribed in some way, in particular, if there were general ratepayer dissatisfaction with a CCO's performance on any matter that gave rise to heightened political concern; and

- the creation of a "compliance burden".

Compliance

6.55

A compliance burden could arise where processes for CCO staff to consult, liaise, and report to Council staff duplicate or render ineffectual the oversight and governance role of the CCO board.

6.56

The Council and CCO governance relationships are evolving. However, we noted a tendency by people we spoke with to focus on formal processes and mechanisms for consultation and monitoring between the Council and CCO staff. We were surprised at how infrequently the extent, nature, and quality of engagement with CCO board members was discussed.

6.57

We are not confident that the Council will be able to move to a more future-oriented and trust-based culture through the use of more formal processes and mechanisms. Ultimately, the mechanism for accountability of a CCO to its owner is through the board. If a CCO is not meeting the Council's expectations, the Council should remove the board, replacing it with members who the Council has more confidence in to act on its expectations.

Council

6.58

We consider that the Council could improve the feedback from the governing body on the CCOs' SOIs. In our view, the feedback should prioritise the input on the CCO's SOI from other parts of the Council to give CCO boards clear expectations about the Council's preferences and priorities.

6.59

A Council Chief Executive who is also appointed as a CCO board member is likely to face conflicts between their duty to act in the best interest of the Council and to act in the best interests of the CCO as a director.

CCO boards

6.60

All CCOs – in particular, those that have a critical part to play in the public's trust in the Council and the achievement of the Council's consolidated LTP and the Auckland Plan – need to understand and demonstrate their commitment to playing their part.

6.61

A board must endeavour to give the Council confidence that it understands the Council's expectations.

15: Auckland Transition Agency (March 2011), Auckland In Transition: Report of the Auckland Transition Agency, Volume 2, page 10.

16: Auckland Transition Agency (March 2011), Auckland In Transition: Report of the Auckland Transition Agency, Volume 2, page 9.

17: Report of the Royal Commission on Auckland Governance (March 2009), Volume 1, pages 474-475.

18: Auckland Transition Agency (March 2011), Auckland In Transition: Report of the Auckland Transition Agency, Volume 1, page 119.

19: See Shareholder Expectation Guide for Council Controlled Organisations, page 17, on www.aucklandcouncil.govt.

20: Controller and Auditor-General (August 2011), Planning to meet the forecast demand for drinking water in Auckland.

page top