Part 1: Why we looked at child poverty

1.1

In New Zealand, an estimated 13.4% of children (156,600) live in households in material hardship – where meeting everyday needs is a struggle. Child poverty has multiple causes, multiple public organisations contribute to responding to it, and there are no simple solutions.

1.2

We considered it important to carry out this audit because of the serious and long-term consequences of child poverty. There is public interest in reducing child poverty but confusion about the different ways that child poverty is officially measured. This has the potential to affect transparency about the government's performance in reducing child poverty.

1.3

We also wanted to understand the work Ministers and public organisations are doing to address the significant inequities in child poverty rates. Māori, Pasifika, and children affected by disabilities all experience higher rates of material hardship (23.9%, 28.7%, and 22.6% respectively) than the overall population of children (13.4% – see Appendix 1).4

1.4

Inequities in the rates of child poverty can lead to inequities in school achievement, adult employment, income levels, and behavioural, health, and cognitive outcomes.

1.5

Dealing with the consequences of child poverty takes considerable public resources and reducing it will take significant investment. It also needs a public service approach that is well governed, collaborative, and integrated, and that enables community-led responses where appropriate.5

Child poverty rates have started to rise

1.6

The Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018 sets out four primary and six supplementary measures of child poverty (see Appendix 2). As required by the Act, the Minister for Child Poverty Reduction has set intermediate (three-year) and long-term (10-year) targets for the primary measures.

1.7

Although six child poverty measures trended downwards between 2018 and the year ended June 2022, there has been a significant increase in five measures since then, including the measure for material hardship. None of the targets that were in place for three primary measures were met in 2023/24.

1.8

The Treasury's Tax and Welfare Analysis modelling for both the 2023 and 2024 Budget Day Child Poverty Reports indicates that the government is not on track to meet the 10-year targets for two of the primary measures.

1.9

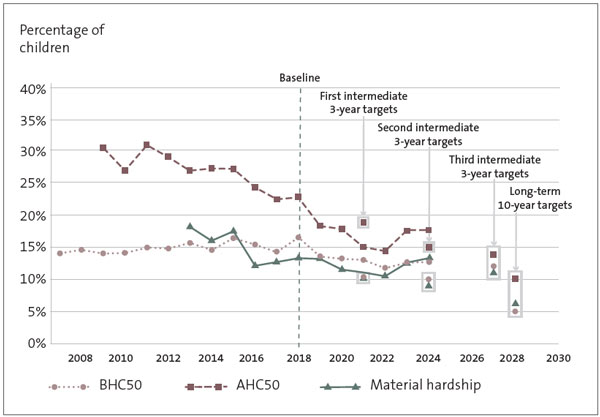

Figure 1 sets out the long-term trends in the three primary measures of child poverty in use and their three- and 10-year targets.

Figure 1

Long-term trends in three primary measures of child poverty and their three- and 10-year targets

Source: Statistics New Zealand (2025), "Child poverty statistics: Year ended June 2024", at stats.govt.nz.

Note: Sampling errors range from 0.9 to 4.3 percentage points.

1.10

The measures based on income before housing costs (BHC50), income after housing costs (AHC50), and material hardship are explained in Part 2 and defined in Appendix 2. The latest intermediate targets (for 2026/27) for these primary measures were set in June 2024. Two of the three targets (for BHC50 and material hardship) are less ambitious than the targets set for 2023/24.

What we looked at

1.11

We wanted to know how effective government arrangements to reduce child poverty are. We looked at what government is doing to respond to child poverty and mitigate the impacts of socio-economic disadvantage, because the Children's Act 2014 requires the responsible Minister to adopt a strategy that addresses both.

1.12

We focused on four public organisations with responsibilities for overseeing progress to reduce child poverty – the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Ministry of Social Development (MSD), the Treasury, and Statistics New Zealand (the agencies).

1.13

We looked at the effectiveness of the governance and management arrangements to reduce child poverty, including planning, measuring, monitoring, and reporting.

1.14

See Appendix 3 for more information about how we carried out this audit.

What we did not look at

1.15

Consistent with our mandate, we did not audit:

- the appropriateness of the child poverty measures, some of which are set in legislation and others defined by the Government Statistician (the chief executive of Statistics New Zealand);

- the appropriateness of the child poverty targets, which Ministers set; or

- the direction set in the Child and Youth Strategy.

1.16

We also did not assess the effectiveness of individual initiatives aimed at reducing child poverty or the effect of other government policies on child poverty rates.

4: "Children affected by disabilities" refers to those living in a household where there is at least one disabled person.

5: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2022), "Briefing: Review of the Child and Youth Well